Cross-Referencing is the overarching task of making cross-references work. It consists of writing

-

parser rules to identify cross-references using the Xtext grammar language

-

export rules using the Export language

-

scoping rules using the Scope language

-

Java functions to support custom naming

-

tests

Cross-referencing is challenging as it requires a very thorough understanding of all the involved DSLs, their structures, visibility rules, interdependencies, etc.

Purposes of this user guide

-

Take the reader to a deeper understanding of scopes and scoping.

-

Describe practical solution patterns and antipatterns.

Xtext language definition and structure

All Xtext languages are defined formally through the use of the Xtext grammar language, a DSL designed to describe the concrete syntax and the abstract syntax tree (AST) of the targeted language. An Xtext grammar consists of

-

an optional reference to an Xtext grammar for a base language to extend,

-

imports of existing Ecore models and optionally one Ecore model to generate,

-

a set of rules that define the syntactical structure of the language.

Together, all the rules define the parse tree. There are four types of rules that each focus on a different aspect of the syntax:

Terminal Rules — define the sequence of characters that make up a certain token; technically a token is a string as produced by the lexer, e.g. the rule for the keyword import or the rule for whitespace:

terminal WS : (' '|'\t'|'\r'|'\n')+;

Data Type Rules — reference terminal rules and data type rules to define a single or a sequence of tokens which gets mapped to an instance of an EDataType, e.g. EInt or an EString like this one:

QualifiedName returns ecore::EString : ID ('.' ID)*;

Enum Rules — define how single keyword tokens get mapped to an enumeration literal in the AST; enum rules are thus like specialized data type rules (since EEnum is a subtype of EDataType), e.g.

enum VisibilityKind : PUBLIC = 'public' | PROTECTED = 'protected' | PRIVATE = 'private';

Parser Rules — reference rules of all types to define how sequences of tokens map to objects (actually EObjects) and their structural features in the AST; technically it defines a subtree of the parse tree

Type : 'type' name=ID ('extends' supertype=TypeRef)? '{' (declarations+=Declaration)* '}';

Terminal rules and parser rules can be nested thus defining more refined tokens (terminal rule) and a more complex token structure (parser rules) that takes the shape of a tree. Data type rules and enum rules define individual nodes of the parse tree rather than subtrees.

The parse tree is a perfectly shaped tree with no cross-links between branches. At runtime, Xtext processes one resource at a time and creates a parse tree per resource.

Cross-reference assignments

One item of particular interest in the context of cross-referencing are cross-reference assignments inside parser rules. Assume we have an input character stream like this:

deliver to mikesHomeAddresses;

In the simple case a cross-reference assignment looks like this one:

Delivery : 'deliver' 'to' address=[AbstractAddress] ';' ;

which means: assign a link to some AST node of type AbstractAddress to the AST feature address which is a non-containment EReference. Note that at this point it has not been determined further exactly which AST nodes of type AbstractAddress are eligible candidates for this, except that the cross-reference text mikesHomeAddresses somehow identifies the node. We will elaborate later on the rules that govern the matching of cross-reference texts (also called link texts) with AST nodes.

The previous example doesn’t specify what rule the parser should use to parse the mikesHomeAddresses token. Xtext will apply a default here and uses the rule ID (which thus must exist) to parse that token. If we don’t want that we can explicitly declare the data type rule (or terminal rule) which should be used, as in e.g.

Delivery : 'deliver' 'to' address=[AbstractAddress|QualifiedName] ';' ;

where the second element in the brackets, QualifiedName, specifies that data type rule or terminal rule. A character stream compliant with the above grammar fragment could be:

deliver to mike.address.home;

It is important to note that, at this point, all that is known about the cross-reference is the link text. But neither has the target object of the cross-reference been identified nor has a real reference (a “pointer”) to it been created.

The Xtext AST

An Xtext grammar definition defines more than just the parse tree which is essentially a tree representation of a linear character sequence (conforming to the syntactical rules of the language, and containing all the whitespace and tokens that are only there to assure correct LL-parsing). The grammar definition also defines a second, more convenient representation of the original character sequence, the abstract syntax tree, AST, which contains only information of a certain semantic value.

Xtext uses the Eclipse Modeling Framework, EMF, to define the AST as a tree of EObjects:

-

typically each called parser rule produces a node in the AST (an EObject),

-

parser rules can contain assignments, that either set an attribute of the node (when assigning a terminal or data type rule to an EAttribute) or define a subtree (when assigning a parser rule call to a containment EReference), or map to a cross-reference of the node (when assigning a terminal rule or data type rule to a non-containment EReference).

So far the AST is also a perfectly shaped tree with no hard references between branches. All the links between nodes are EMF containment references defining a container relationship between a node and its child nodes. Note that containment references are special insofar as they are bidirectional, i.e. the children have a reverse reference that links back to their parent (container); moreover, when a child node is removed and discarded by releasing a containment reference, all its children (and transitively all its children’s children) linked through containment references are also discarded at the same time. A given containment link always links to a valid node of the tree because it inherently makes up one parent-to-child node association of the tree.

Besides the containment references the AST also features — as hinted to above — cross-references to arbitrary nodes in the AST. However, cross references are not containment relations, i.e. cutting a cross-reference does not harm or discard the referenced node, and cross-references can be unresolved (temporarily or permanently). The remainder of this document mainly deals with establishing and managing cross-references in the AST.

Xtext resources

Behind the scenes, the nodes of the AST are linked back to nodes of the corresponding parse tree (which, by the way, is not an EMF tree). Both the the AST and the parse tree are contained by an Xtext resource. So, an Xtext resource is a sophisticated, multi-dimensional implementation of a DSL source file which includes a lexer, parser, linker, and serializer to support loading a model from text (i.e. parsing) and saving a model to text (i.e. serializing). In the following we will refer to Xtext resources as just “resources” because these are the only ones we care about at the moment.

Proxy objects

One of the problems with cross-references (this doesn’t apply to containment references, see below) is that the object referenced by a cross-reference text (e.g. the a in String b = a;) might not exist at all leaving us with a dangling reference. This is true for both internal cross-references resolving to objects within the same resource and external cross-references resolving to objects in other resources. In the AST these unresolved cross-references show up as EMF proxy objects.

Lexer, parser, linker

From an Xtext grammar definition, Xtext generates a parser that processes source files in three phases.

-

The lexer turns the character stream (source file) to a token stream

-

The parser first turns the token stream to a parse tree and an AST

-

The linker processes all cross-references by installing proxies which when accessed should resolve to the desired object

The logic for exactly how a proxy for a cross-reference resolves to the correct target is not part of the Xtext grammar definition.

Example

The following fragment of Java code

{

String a = "x";

String b = a;

}

can be covered by this Xtext grammar fragment The real Xtext grammar for Java would be much more complex of course.:

Block : "{" (decl+=Declaration ";")* "}";

Declaration : "String" name=IDENT "=" (val=LITERAL | ref=[Declaration]);

terminal LITERAL : '"' ( !('"') )* '"';

terminal IDENT : 'a'..'z';

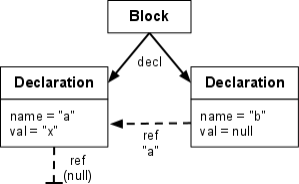

Parsing and linking of the Java fragment would result in the following AST (solid arrows depict containments, dashed arrows cross-references):

DSL Developer Kit uses a lazy linker that defers most of the work to later:

-

in a first phase the linker traverses the entire AST of a resource and installs an unresolved proxy object as the target of each cross-reference. The URI of these proxies is a special kind of URI that (a) marks the proxies as unresolved Xtext cross-references, and (b) contains enough information to perform the actual linking at a later point in time.

-

in the second phase, when the real target object of a cross-reference is requested – the current target only being a proxy – the linking service is invoked via the containing resource. The linking services uses the information encoded in the proxy URI to find the actual target object, then replaces the proxy by the target object provided the target object can be located at all.

Scoping

In the above case it is pretty obvious which a should be the cross-reference target of b, however, in the next Java example, someone had to define some rules at some point to ensure that b is going to be assigned the value of parameter a instead of the value of field a:

class C {

String a = "x";

void m(String a) {

String b = a;

}

}

Defining these access rules is known as scoping. Scoping thus defines what is in scope at any point in time. Scoping is only necessary for cross-references but not for containment references.

A good way to think about what is in scope is to imagine what proposals content assist (Ctrl+Space) should come up with at a given location in the text. In the following Java example, the ?-markers represent points where the content-assist proposals are to be computed:

class C {

static String a = "x";

String b = ?;

int i = ??;

void m1(String c) {

String d = ???;

}

String m2(String a) {

return ????;

}

}

Scope chaining

Scope chaining (also called scope nesting) is a concept to implement shadowing and to modularize scopes into logical reusable sets. In the above example, the scope for ??? is {c} plus anything in the surrounding scope, i.e. {a, b, i, m2(), toString(), clone() …} combined in such a way that the elements in the inner scope have precedence over elements with the same name in the outer scope. Hence the scope for ???? is the set {a} chained to the set {a, b, i, m2(), toString(), clone() …} where the parameter a has precedence over the declaration a which thus appears as hidden.

Chaining scopes has the advantage that the rules for a given scope only have to be stated once and can be re-used either by child scopes or any other scope definitions.

Scope language

It may have already become obvious – and if not it certainly will – that scoping for a given Xtext language (= target language) is not for the faint of heart and that even getting it right from a conceptual point of view is a pretty good challenge. But implementing a set of presumably correct scoping rules in Java is a shaky bet at most: in the best case you make no errors. And then there is all that test code to write … Not something we want to be wasting our time with and reason enough to formalize scoping for Xtext such that scoping rules can be expressed in a higher-order language called scope. Not surprisingly, the main concept of scope is the scope definition (short: scope) . A scope definition declares which objects are in scope within a number of given contexts (where a context is defined by a parser rule of the target-language grammar). Technically, the scope language is just an Xtext DSL designed for

-

the definition of scopes and elements in scope for a target language,

-

the generation of Xtext components that implement the defined scoping.

Scoping vs. linking

Scope computation is a prerequisite for linking: the linker simply asks for all the elements in scope, then it chooses the first element (in order of precedence as defined by the scope chain) with a matching name. The elements returned by the scope provider are not the real objects but rather object descriptions providing a getName()method.

References across resources

So far none of the examples included cross-references to elements in other resources such as when a Java import statement or a static method invocation references a class in a different package by its fully qualified class name.

Global scope

As described cross-references can either resolve to local objects (within the same resource) or to external objects (objects within other resources). Many cross-references can actually end up being resolved to local or external objects, depending on the actual link text. As an example consider the Java language again: In any expression the first identifier could be the name of a locally defined variable or method, but it could also be the name of a class defined in another source file. Typically there is a defined precedence order which allows a local object to shadow an external object. And typically there are also naming conventions (e.g. Java classes should begin with upper case letters while methods, fields, parameters, and variables should begin with lowercase letters) to guard against such clashes.

To make this problem manageable when defining the scope for a given cross reference the scope is usually divided into a local scope and a global scope which are then chained together to form the complete scope for the cross-reference. This often also has the advantage that the global scope can be reused when defining the scope for other cross-references.

Xtext Index

One of the problems with external cross-references is the sheer quantity of potential target objects. Loading a resource each time a cross-reference is resolved is not practical, especially since the resource containing the target object may not be known up front. And neither is keeping all the resources loaded in memory. The solution is the Xtext index, a dictionary that lists all the sources of the complete model together with their name and URI and for each source provides descriptions for its exported objects (declarations accessible to the outside), again with name, type and URI.

In order to resolve a cross-reference in the global scope, it suffices to query the index which returns the description(s) of the matching element(s) or the empty set if no such element is present. So, instead of on the fly parsing hundreds of resources to compute potential link targets, we can query the index for a set of candidates for the given criteria.

The returned information — mainly name and type for each matching element — is usually enough to determine the actual cross-reference target. Then a proxy object of the appropriate type and URI is attached to the reference in the AST. When access to the actual AST elements of the referenced resource is needed, the proxy is resolved, which triggers the loading (parsing and linking) of the referenced resource.

Export language

As a prerequisite of querying the index we have to make sure that the elements we hope to find are somehow inserted into the index. This is the “raison d’être” of the export language. Language elements that are not exported from one source are not visible to other sources. So why not simply export the entire AST? — This would bloat the index to the point where it would not provide any performance gain in accessing individual elements. Thus exporting is a careful balance of convenience vs. access speed. Also, resources that export elements are usually referenced by other resources that make use of those elements. Changes to the exporting sources often mean rebuilding (i.e. mainly re-linking) the depending resources to mark cross-referencing issues immediately. But not every change to an exporting resource requires rebuilding the depending resources: adding new exported elements requires at most a rebuild of resources that have unsatisfied cross-references (they could now become valid). In addition changes to non-exported elements can cause rebuilds, e.g. procedure parameters are usually not exported but if an additional mandatory parameter is added to a resource, then all sources containing invocations of this procedure should be rebuilt. A mechanism called finger printing is used to quickly determine whether a given change causes rebuilds and for whom. See the export documentation for details.

Technically, the export language is just another Xtext DSL designed for

-

the definition of which elements of a target language should be exported,

-

the definition of what changes to a resource cause all depending sources to be rebuilt,

-

the generation of Xtext components that implement the defined behaviour.

Index anatomy

The Xtext index is a store knowing about all the elements of all sources that can serve as targets for cross-references defined within other sources. Or more precisely: the index consists of descriptions of all the globally linkable elements of all sources within an Eclipse workspace. The Xtext index is populated by the Xtext builder which determines the exported elements of a resource by executing the export rules for the source type of the resource.

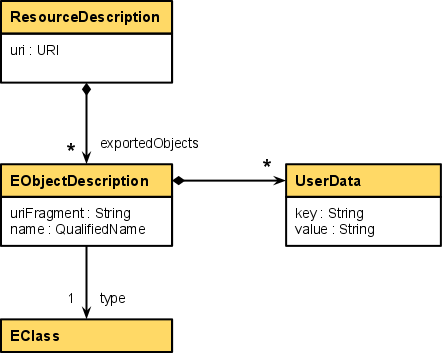

The Xtext index, among other things, holds descriptions of resources and of their exported objects:

Note

-

how the index contains EObjectDescriptions instead of the real EObjects

-

that the only information stored about an EObjectDescription is its name, URI, and type; optionally it may also be associated with freeform string user data entries

-

that the object’s name is a qualified name, as in e.g. ClassName.MethodName

-

how each object is associated with its type (expressed as an EMF EClass)

EClasses support subtyping. Similarly the Xtext index provides operations to find all EObjectDescriptions matching a certain type or supertype. This relationship is used heavily when querying the index.

The index also supports object name prefix matching. If all entities in a package are exported with a qualified name starting with the package name ‘com.avaloq’ we can use the following scope expression to find all those entities:

find(Entity, key = 'com.avaloq.*')

Note that the ‘*’ wildcard is only allowed at the end of the matching string; i.e. there can only be one asterisk and it must occur at the tail.

Name matching

DSLs can sometimes reference elements under various names from within the same source. This breaks with the common rule followed by most general purpose programming languages that the exporter of an element determines the name under which the element can be referenced. If an element is known under a single name (usually a qualified name), even if the computation of this name varies from one kind of exported element to the next, then all the respective export rule needs to do is to define that naming scheme. Here’s an example of an entity export form an export file:

export lookup mydsl::Entity as name { ... }

Then the find clauses in the scope rules need to use the same naming scheme and name matching is trivial. Expressing “same” is extremely easy as shown in this example :

scopeEntity#entityReference {

context ScopeElement = find(mydsl::Entity) as export;

}

export ensures the exported name (QualifiedName) of EObjectDescription is used for name matching.

The as clause can even be used in export rules for elements that have no name themselves:

export lookup mydsl::AbstractEntity as qualified this.getName() { }

In this example we also see the keyword qualified being used, which signifies that the expression that follows returns an already qualified name which the object should be exported under. Normally (without the qualified keyword) the name would be prepended by that of the nearest exported parent object. Note that the keyword lookup tells the index implementation to expect lookups that might discover this element so the name will be taken into the lookup map. If lookup is not specified, then doing find or an index query to search for this element is forbidden.

Exporting multiple names

If, however, an element is exported under various names, then we are facing a capacity problem for EObjectDescription which can only cope with a single name.

Using UserData is an acceptable solution. EObjectDescriptions can make use of the generic key–value structure of UserData and have as many UserData objects as they like. And they do, as shown in this CodeTabData export rule:

export lookup myDsl::Entity as this.getQualifiedName() {

field key;

data user_id = this.getUserReference();

}

Before we delve into the analysis of the above export rule, it helps to contemplate the parser rule for Entity for moment so we can tell later which of the attributes and methods of Entity stem from the grammar and which were added to satisfy linking needs:

Entity :

"entitiy" name=ID '(' key=INT ')'

( "user_id" userId = STRING )?

;

Analysis of the export example above:

-

the getQualifiedName() function is a method on Entity and has been implemented manually in EntityImplCustom. The value returned by getQualifiedName() is stored in the name field of the EObjectDescription in the index.

-

the field key of the Entity:

-

see the export documentation about what the field and data keywords do in the export clause.

Custom name functions

Whenever an object needs to be referenced via a name under which it was not exported, but the exported name can be computed from its index user data, scope rules can use a custom name function to do this as in the following example:

scopeEntity#entityReference {

context ScopeElement = find(mydsl::Entity)

caseinsensitive as factory getUserIdFunction();

}

Analysis:

-

String comparison in index lookups is case insensitive

-

factory functions allow calling custom name functions (returning NameFunction) defined as Xtend extensions

-

a single name function getUserIdFunction() is listed but multiple are allowed. The entities returned by the find clause are thus added to the scope only under user_id:

-

the getUserIdFunction() bears absolutely no magic and is implemented in Java and has been imported into .scope file.

private static final INameFunction USER_ID_FUNCTION = new INameFunction() {

public QualifiedName apply(final EObject from) {

if (from instanceof Entity) {

return QualifiedNames.safeQualifiedName(((Entity) from).getUserId());

}

return null;

}

public QualifiedName apply(final IEObjectDescription from) {

return QualifiedNames.safeQualifiedName(from.getUserData(EntityResourceDescriptionConstants.ENTITY__USER_ID));

}

};